What are you looking for?

Circus careers study

Circus Centre, together with the Department of Culture, Youth and Media, commissioned a study on careers of circus artists.

Related articles

With the results of the study, the department wants to set to work to sustainably support the further professionalisation of the circus sector via an accompanying policy.

'What actions can the Flemish government take so that (semi-)professional circus artists within the, distinctly internationally oriented, circus sector are given optimal opportunities to develop their careers with attention to both artistic, pedagogical and support profiles as well as to reconversion?'

That is the central research question. Circus Centre will also use the results of the research to feed the landscape drawing circus arts.

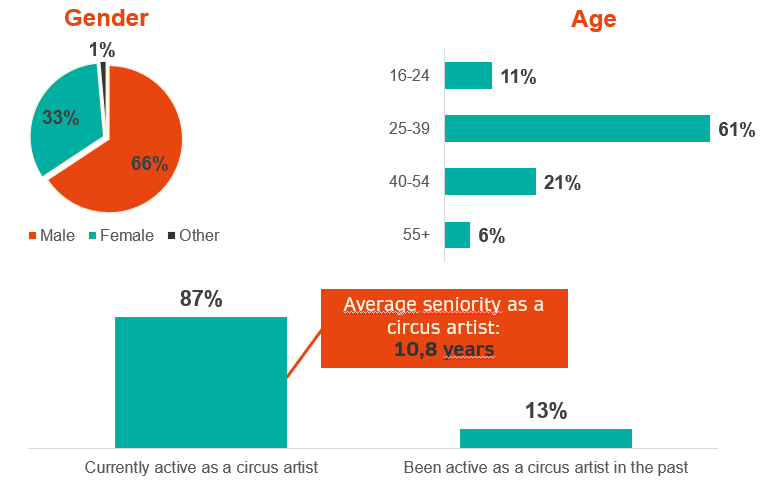

To visualise the career paths of circus artists and to uncover the underlying factors of career dynamics -and to create an empirical basis for this- a survey was organised aimed at circus artists in Flanders.

The survey was distributed in September - October 2022 by different actors in the Flemish circus field (such as DJCM, Circus Centre, respondents of the exploratory interviews, members of the sounding board group, ...) and promoted at an artists' meeting. 70 respondents started the survey, and 52 of them completed it to the end. The average completion time was 15 minutes.

POSITIONING OF THE STUDY

In recent years, several policy developments (the original Circus Decree in 2008 and a renewed decree in 2019) have provided an impetus leading to the professionalisation of the circus sector. In this context, this study aims to identify the position of circus artists and the opportunities for career development.

In specific terms, this study aims to provide an insight into (1) the policy and professional context in which circus artists develop their careers, (2) the progression of careers of professional (or semiprofessional) circus artists, (3) the existing bottlenecks and levers in relation to sustainable careers of circus artists, and (4) forward-looking initiatives that government, Circuscentrum (supporting organisation for the circus sector) and the sector itself can undertake to make careers more sustainable.

A mix of research methods was employed, namely a brief desk study, 2 international benchmarks, 9 exploratory in-depth interviews, an online survey targeting circus artists and 4 focus groups with circus artists and circus professionals. The progress of the study was monitored by a steering board with members from the Department of Culture, Youth and Media (DJCM) of the Government of Flanders and Circuscentrum. The results were tested in the interim and further explored with a sounding board group consisting of actors from the DJCM, Circuscentrum and the circus field (circus artist, management agency, dramaturg, creation space, cultural centre).

CONTEXT SKETCH

The most important actors active within the Flemish (and international) circus landscape are:

- Circus companies: Artists are often active in their own company and/or collaborate in productions of other artists/companies (whether subsidised or not).

- Circus schools: These are responsible for providing circus-related education and on that basis sometimes also focus on other functions such as creation, production, presentation and participation. For many circus artists, a circus school forms the seed of their career as a circus artist and/or a circus school provides a second source of employment as a teacher.

- Educational institutions: In addition to circus schools (in leisure time), also formal education is available to become a circus artist: the secondary education programme specialising in circus skills at the Lemmens Institute in Leuven, higher education at the ESAC in Brussels, or other higher education programmes abroad.

- Circus creation Spaces: A place where both circus artists and circus companies can develop, deepen and reorient themselves artistically. In Flanders today, there are four creation spaces that receive structural funding.

- Circus festivals: In various ways, circus and street theatre festivals contribute to the development of sustainable careers for circus artists. They are important places where artists share their work with the audience.

- Circuscentrum: Circuscentrum is the sectoral ‘centre of support’ within the Circus Decree and fulfils the following tasks under the terms of that decree: practical support, practical development, public perception and promotion, and platform.

- Management agencies and booking offices: Management agencies and booking offices support circus artists with the business and organisational aspects of their work. The supply of such agencies is limited.

- Arts centres and cultural centres: As for the arts centres, we note that in principle there are no ‘partitions’ between the Circus Decree and the Arts Decree. Actors under the Arts Decree can also take a role in supporting circus artists. Cultural centres are supported at the local policy level. A growing number of them are including circus in their programming.

- International partners: The network supporting Flemish circus artists also transcends regional and community boundaries. Circus artists and companies turn to international partners for performance and co-production opportunities.

The main policy instruments that play a role in the career development of circus artists are:

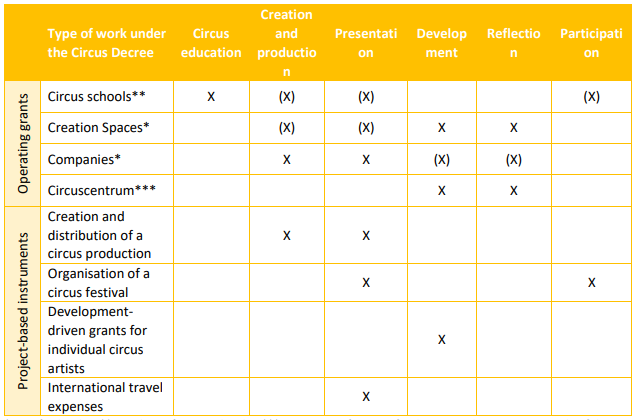

- The Circus Decree: The Circus Decree of 2019 provides eight lines of funding for which applications can be submitted. This may involve structural funding, which is also called operating subsidy. This is awarded for several years and takes the form of a subsidy for the entire operation of an organisation, and for companies, creation spaces, circus schools and a circus centre in particular. The other funding lines are project grants, which are awarded to a well-defined project taking place for a defined period of time (a maximum of three years). These may include a project grant for the creation and distribution of a circus production, the organisation of a circus festival, development-driven grants for individual artists or funding for international travel expenses.

Figure 1: Subsidy instruments under the Circus Decree linked to functions / core tasks

* New funding line ** Devolution from youth policy *** As a centre of support for the sector, the generic core tasks of the Circuscentrum are ‘practical support, practical development, platform, public perception and promotion’ Source: IDEA Consult based on the Circus Decree and the Circus Decree Explanatory Memorandum.1

- EU funding: European-level initiatives such as Creative Europe, Erasmus+ and Interreg. Various circus-specific networks (Circostrada, EYCO, CARP, FEDEC, etc.) that fulfil a networking role and 1 See https://www.vlaanderen.be/cjm/nl/cultuur/circus-vlaanderen/subsidies-ci… provide knowledge and practical development on an international level are supported within the EU context.

- Additional forms of funding: Tax Shelter, ParticipatieMaatschappij Vlaanderen, Cultuurkrediet and Crowdfunding.

- Artist status and art work benefit: Circus artists with “artist status” are entitled to benefit from rules in the unemployment regulations that are designed to accommodate the periods between paid projects. From 1 September 2022 onwards, this scheme was extended to "art workers," so that individuals who provide artistic or technical support to artists also qualify for it. For (circus) artists who perform artistic services only on a small scale, the artist card exists. This card allows the use of the small fee scheme (KVR). The advantage of this is that the (artistic) performances do not have to be declared to Social Security.

CAREERS OF CIRCUS ARTISTS

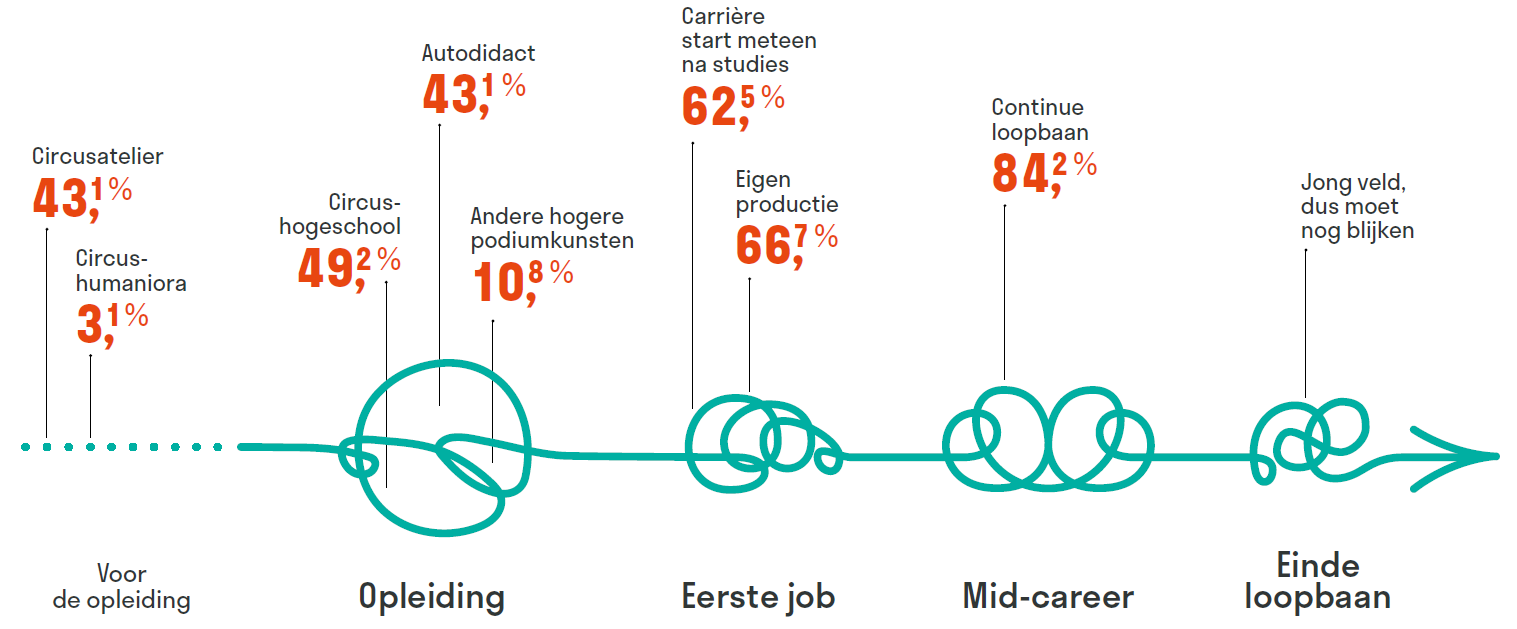

Before starting a professional career, the passion for circus is ignited and technical and artistic skills are built up. In the case of many circus artists, the circus bug bites at a young age. 43.1 percent of circus artists who answered the survey used to take part in classes in a circus school. There are also a number of pathways that aspiring circus artists can take to prepare for circus-related higher education programmes. There is one secondary education programme specialising in circus in Flanders. Finally, the ESAC and the Circuscentrum organise the annual young talent internship, which prepares young people for the admission tests of circus-related higher education programmes.

Many circus artists then follow a circus-related higher education programme (in Brussels or abroad - after all, there is no higher circus education in Flanders). In the survey, 49.2 percent had followed a circus-related higher education programme. The qualitative part of the study cited that in recent years in particular, circus artists who are professionally active became so after following a circus-related higher education programme. For its part, the older guard often started work without having received formal circus-related education or training. Indeed, the provision of circus-related education and training used to be less widely known and less extensive. In addition to circus-related higher education programmes, the circus artists interviewed reported that there is also an extensive range of in-service training and workshops such as master classes, free training in circus schools and circus conventions.

Most professional (and semi-professional) circus artists start young. On average, circus artists are 24 years old when first employed as a circus artist. Of all the circus artists who completed the survey, 62.5 percent started as professional (or semi-professional) circus artists immediately after completing their studies. Among the group that received higher circus or performing arts education or training, that proportion is a lot higher: 78.4 percent.

Most circus artists got started by creating a circus production of their own (66.7%). This can be done alone or in collaboration with other students or graduates within a production group/collective. One in four circus artists at the start of their career was asked to join another company. Their first circus production of their own after starting out on their career usually took place without external financial support. If any support was received from the circus sector at all, the most common form of support for the first production was mostly non-financial.

In particular, artistic and technical skills have been found to be hugely important when starting out as a circus artist (88.9% say they helped). The network is another important factor when starting out. 59.3 percent of circus artists surveyed indicated that good advice from other circus professionals helped them, and 48.1 percent specifically indicated that the network they built helped them.

The majority of circus artists have remained continuously employed as circus artist. Most of the circus artists (84.2%) who took part in the survey reported that they had a continuous career, i.e. they have always remained employed as circus artist, though this was often combined with other jobs. In order to continue working effectively as a circus artist after starting out on the career, having a professional network (in which circus festivals in particular have been found to play an important role) and sufficient performance opportunities were found to be important (these are necessary to ensure continuity in income). In addition, adequate opportunities for artistic development and deployment, sufficient resources to create new work and direct financial support are also important levers. “Eagerness and perseverance” were also cited as important levers that enable individuals to remain employed as a circus artist.

But some circus artists also leave the sector (sometimes on a temporary basis). The main reasons for leaving the sector (temporarily or otherwise) appear to be a lack of financial security, coronavirus, an injury, inadequate opportunities to perform, grants not awarded, an unattainable work/life balance, a surfeit of non-artistic activities that have come to be involved and emotional strain. The focus groups show that it is often a combination of several factors that are demotivating and are causing the "eagerness and perseverance" to hit their limits. Life on tour has also been found to be difficult to combine with a family. Outsourcing certain support tasks may be a solution. But in a sector where budgets are already tight, this is often not financially feasible. Finally, limited opportunities to perform may play a role in the case of circus artists in a later stage of their career. As careers progress, stricter artistic selections are made, and established artists sometimes receive fewer opportunities to perform because of the focus on “the new crop” or on popular names.

Most circus artists want to continue working in the circus sector in the future, although for one in five, this is subject to conditions (e.g. feasible work-life balance, environmental sustainability, a solid financial basis, physical and mental wellbeing, management office support, sufficient resources for new creations, opportunities for artistic development and opportunities to perform, etc.). Most circus artists are therefore satisfied with their careers thus far. Those that responded to the survey gave an average score of 7.7 out of 10. Satisfaction is a lot lower in terms of progress in terms of job security and financial income. Only half are satisfied in that regard.

EMPLOYMENT OF CIRCUS ARTISTS

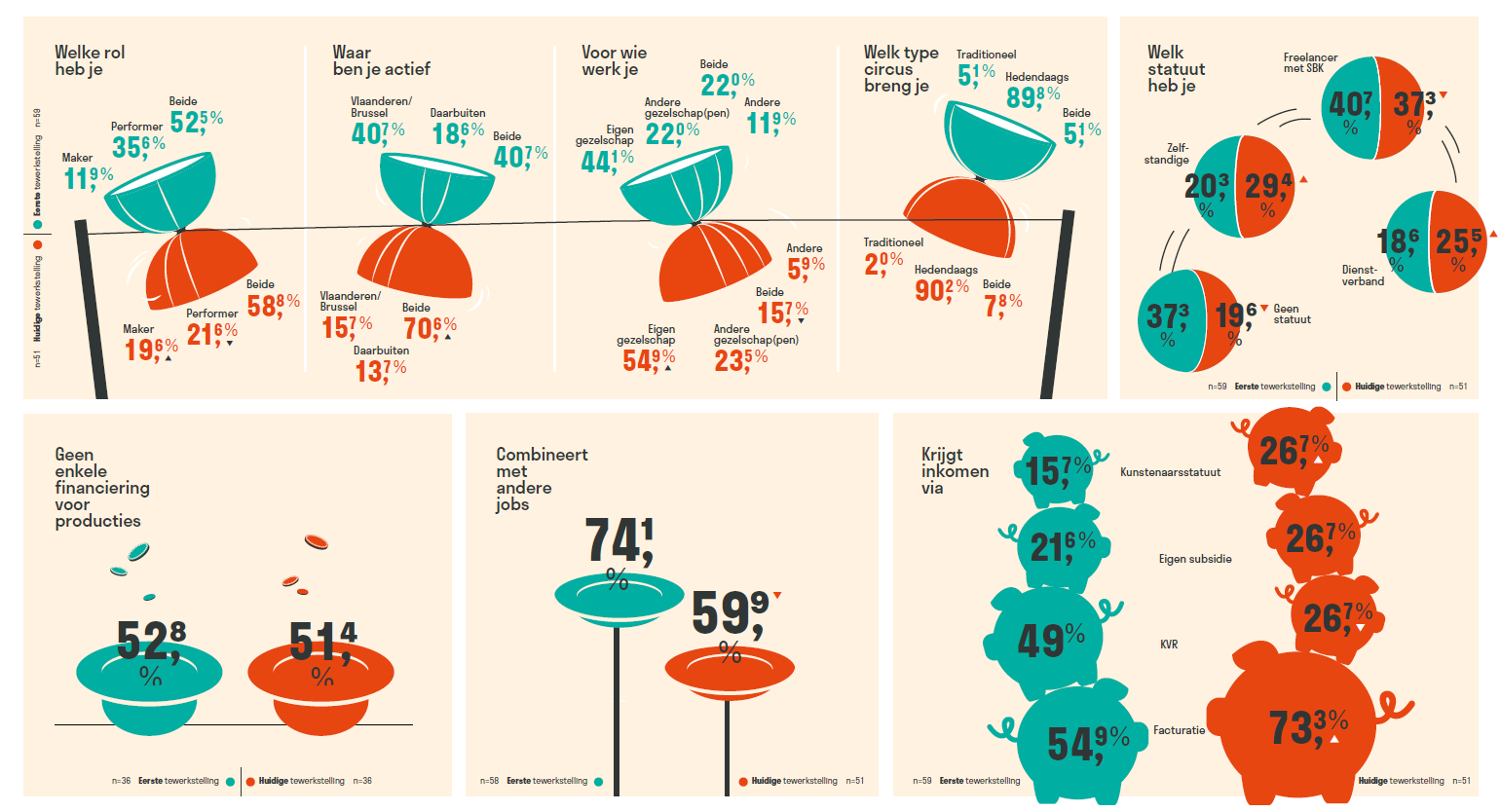

The survey identified characteristics of both initial and current employment as a circus artist:

- Freelance is the most commonly used status. In their current employment, 37.3 percent work on a freelance basis (40.7% when first employed). In addition, 29.4 percent are self-employed (20.3% when first employed) and 25.4 percent are employees (18.6% when at the start of their career). The proportion working without status has dropped sharply compared to when first employed (19.6% versus 37.3% at the start of their career).

- In most cases, creating and performing are combined. 58.8 percent work both as creators and performers (52.5% when first employed). 21.6 percent operate exclusively as performers (that was still 35.6 percent when first employed) and 19.6 percent operate exclusively as creators (11.9 percent when first employed).

- A large number of circus artists start a company of their own. 54.9% are employed by their own company (that proportion was 44.1% when first employed). A further 15.7 percent work in both their own and in one or more other companies (compared with 22% when first employed).

- Most circus artists have international careers. 70.6 percent operate both inside and outside of Flanders and Brussels. Only 15.7 percent are active exclusively within Flanders and Brussels, compared to 40.7 percent at the start of their careers. As their careers progress, artists who started out in our region successfully manage to internationalise.

- Their job as a circus artist is often combined with another job. When first employed, as many as 74.1 percent combine their job as a circus artist with another job. In current employment, the proportion combining jobs has fallen sharply, although it remains high: 56.8 percent still combine employment as a circus artist with another job.

- The most commonly used remuneration systems are billing for artistic performances, artist status and the small fee scheme (KVR). In their current employment, about three-quarters of circus artists remunerated for their work by billing for artistic services (including buyout sums). In the case of circus artists employed for the first time, that figure is only 54.9 percent. In addition, 26.7 percent have artist status (versus 15.7 when first employed), 26.7 are claiming a personal grant or project grant (versus 21.6% in their current employment) and 26.7% make use of KVRs (versus 49.0% when first employed).

- More than half of the artists make productions without external funding. This may include the fact that as far as the costs associated with creation and production are concerned, neither subsidies nor co-production contributions were used. The production costs were paid from the own pockets, but may have later generated income from buyouts. it is worth noting that the proportion working with unfunded productions is almost the same when first employed as in the current employment (52.8% versus 51.4% when first employed).

BOTTLENECKS AND LEVERS FOR SUSTAINABLE CAREERS

The bottlenecks and levers that were identified as a means of building a sustainable career as a circus artist are structured according to 5 dimensions of sustainability: economic, artistic, environmental, human and social sustainability.

- Economically sustainable careers

With the development of the Circus Decree, grant opportunities (and amounts involved) have been systematically expanded in recent years. Yet work as a circus artist continues to go hand in hand with generally low wages. For example, due to limited budgets, there is great pressure on the amount of buyout fees and also limited transparency on the pricing of those buyout fees. Although fair pay & fair practice receive more attention than in the past, fair pay in the pricing of buyouts does not yet appear to be as well established. What is more and on a practical level, it appears that even with grants, not all of the work performed is reimbursed (development-oriented activities, but also administration, planning, communication, logistics, website management, etc.), despite the possibilities provided for in the Circus Decree. Today, the three companies that chose to apply for structural support under the decree do have a broader financial base to fall back on. Most artists have not yet taken this step and rely on project grants. When preparing a grant application, circus artists will also regularly not submit full actual costs, in the hope that they will be more likely to receive a positive response. Inadequate knowledge about how to prepare a grant application also complicates access to financial support.

What is more, the income of circus artists is often uncertain and unstable. Circus artists can never be sure whether grant applications will be accepted, nor whether they will be able to find enough venues in which to perform. Artist status can cushion the instability in income to some extent, but it still involves a lot of administration and burden of proof which creates uncertainty for some. There is also little social protection for circus artists.

Creating opportunities to perform is an important lever when it comes to providing continuity of activities and therefore careers for circus artists and circus companies. Today, many initiatives are therefore focusing on ways of increasing the opportunities to perform. Showcases and festivals are essential as places where (international) programmers can see new work. There are several initiatives – especially within the sphere of operation of Circuscentrum, in addition to festivals and creation spaces – to engage in visibility and in the promotion of artists, companies and productions. In recent years there has also been a stronger policy focus on the international promotion of circus from Flanders (in countries such as France).

Finding sufficient opportunities to play can still be a challenge, however. Programmers – both at home and abroad – have limited budgets, so audience attendance is very important. Time for prospecting is also becoming scarcer. That makes it harder for smaller, unknown companies to get opportunities. A growing openness to contemporary circus in Flanders can now be observed, both among presentation venues and the public, but there is still growth potential. In addition, the infrastructure of presentation sites is often a thorny issue. The halls of cultural centres are not always equipped to accommodate circus performances.

Traditional circuses do not operate on buyouts; they perform at their own risk. This brings with it a high degree of uncertainty. One of the main bottlenecks is the increasing pressure on pitches (fewer of them, smaller, more stringent, including with regard to posters and visual publicity, etc.). Nowadays, Circuscentrum is already acting as a point of contact and mediator for the local government and supralocal initiatives.

Finally, a lot of circus artists have difficulty coming to terms with the business aspects involved in being a circus artist. On the one hand, a lot of circus artists lack these skills. Circus-related education and training programmes also only pay limited attention to this. On the other hand, circus artists often lack the time to focus on remedying this. Project-based work creates little scope for business professionalisation.

Support in the business aspects therefore also forms a lever. However, the provision of booking offices and their affordability is limited for circus artists. There is a great need for organisations that ensure continuity in the activities of circus artists, not in a project-based way, but on a 'pathway-based' basis. The sector is exploring these and other possibilities, although the options within the current Circus Decree in this area remain too limited at present and do not invite forward-looking work on innovative solutions.

- Artistically sustainable careers

Several initiatives have been developed that are contributing towards more sustainable career development from an artistic perspective. These include operating subsidies, project grants for creation and distribution and development-driven grants. In addition, at creation spaces, circus schools, during festivals, at conventions, etc. there are a wide range of informal opportunities to develop artistic and technical skills during one's career, both collectively and individually. By means of residencies and co-productions, creation spaces – and in principle even festival organisers – can also support research and development. Finally, the Circuscentrum, as a centre of support, is committed to providing practical development and support. Both traditional and contemporary circuses have access to these forms of support.

Yet bottlenecks impeding artistic and technical development are also being identified. The scope of research and development tools remains too limited. To create a long-term artistic perspective for themselves, circus artists need to combine the offerings of various supporting organisations. When doing that, they are dependent on (many different) gatekeepers. Coordination time and a good knowledge of the sector are therefore required. And finally, there is a shortage of circus teachers with the right combination of artistic and pedagogical skills.

- Evironmental sustainability

Environmental awareness is also playing an increasing role in career choices, especially in a sector that is so distinctly international. For example, there are circus artists with international careers – within which the international mobility of productions is important as a means of ensuring opportunities to perform – who are phasing out this form of internationalisation and deliberately focusing more on activities in Flanders and Brussels. Others are focusing on more sustainable forms of international travel (train, car, etc.). One opportunity that can be further developed in that regard is to make visible the opportunities and ecosystem in Wallonia and in neighbouring countries.

Attention to environmental sustainability is also increasing in professional decision-making frameworks (such as Perform Europe as an EU pilot project to support sustainable international tours of circus productions). Beyond that, however, the current policy frameworks include hardly any incentives to encourage environmental sustainability.

- Humanly sustainable careers

By human sustainability, we mean inclusion in the circus sector, as well as the feasibility of working as a circus artist for one's entire career.

While there are many examples of how circus can be an engine of inclusion and participation, the professional circus landscape – in Flanders, but also beyond – is strikingly often described as a lacking in diversity, a "cliquish" sector in which many exclusionary mechanisms are at play. In the study, the bottlenecks identified are related to gender equality and the inclusion of people from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds and of those with functional disabilities. Initiatives to make the circus landscape more inclusive are increasing, but they remain incidental/experimental.

There are also major challenges when it comes to ensuring that the work itself is actually feasible. Currently, there are hardly any levers when it comes to ensuring a better work-life balance. Responsibility for this lies with various circus organisations (festivals, creation spaces, other residency programmes). When developing processes and formats, they need to be more mindful of the fact that artists are also parents and have families (e.g. residencies for artists with families). Also, the creation process is perceived as emotionally taxing and the physical strain and the risks to the bodies of performing circus artists cannot, for that matter, be denied. There is a need for proverbial safety nets to limit the physical and mental risks incurred by artists.

Finally, it is important to ensure that individuals develop sufficient, and sufficiently valuable, assets to facilitate a change of position or employment, namely, competencies that enable them to take further steps in their career (this includes artistic, business, social, as well as other relevant skills). Not only to grow and develop their career, but also because of the great uncertainty that characterises the career of a circus artist. Circus artists generally do not appear to have a concrete idea of other directions they can take their career if it is no longer sustainable to remain active as a circus artist. At the same time, the professionalisation of the circus sector and the passing on of craft, technique and expertise will benefit greatly if circus artists reorient themselves within the circus sector.

In traditional circuses, there is in any case no separation between life and work. The human challenge lies mainly in ensuring educational opportunities for circus children.

- Socially sustainable careers

By social sustainability, we mean developing lasting relationships and networks, which is very important in the careers of circus artists. Various research steps have identified the strong (internal) networks that exist within the circus landscape in Flanders, as well as the importance of support from both one's group of friends group and from a diversity of organisations in the circus landscape.

In Flanders, extensive opportunities exist to build the network. Circus schools, creation spaces, festivals, Circuscentrum initiatives, etc. are the places where circus artists meet, interact, strengthen each other among peers. Many circus artists also develop an (international and multidisciplinary) network through circus training and interdisciplinary training such as dance and theatre. International actors also play an important role within career paths of circus artists.

However, it remains the individual responsibility of circus artists to invest in the network. Finding your way in this landscape of relationships requires certain social and networking skills. It also requires the time and capacity to invest in network development. In order to ‘unburden’ artists in that regard, there is a very great need for management agencies, booking agencies and distribution agencies that can invest in building contacts and use their network to promote and distribute multiple artists. Specific attention needs to be devoted to linking up the networks in Flanders with international networks. After all, gaining a foothold internationally is not so easy, according to the artists surveyed in the interviews.

FUTURE CAREER PATHWAYS

Based on the findings in the survey, a number of future pathways were formulated, again structured according to the 5 dimensions of sustainability.

To make careers economically sustainable, our suggestion is that:

- a more diverse range of activities by circus artists should become better paid: fair pay & fair practice principles should continue to be mainstreamed and institutionally embedded, projectbased subsidies should be functionally broadened, awareness-raising and signposting towards forms of additional funding should be improved, further clarification should be provided as to why the Circus Decree is especially open to non-profit organisations and possible incentives for profitmaking initiatives should be explored.

- scope should be provided for a more diverse range of organisational models: organisations that adopt a "pathway-like" approach to provide continuity in circus artists' activities, either by providing all-in support or by helping artists connect the various tools and instruments within artist-run or artist-centred structures.

- there should be a focus on the creation of performance opportunities by increasingly raising awareness, amongst local government and local actors, of the traditional circus, that the focus on investing in (collective) promotion and performance opportunities, both at home and abroad, should continue and that project subsidies purely for distribution purposes and in order to strengthen the image and awareness of contemporary circus among the general public should be made possible.

- existing sector initiatives related to strengthening business skills among circus artists should be consolidated and that increased attention should be given to these skills in educational programmes.

To make careers artistically sustainable, our suggestion is that:

- the existing offering in terms of artistic/technical development should be continued and participation in these activities should be remunerated more effectively by clearly communicating the possibilities that exist within the current funding categories under the Circus Decree and possibly, in the longer term, by interpreting the "development" function more broadly whenever the decree is revised.

- With regard to artistic sustainability, we also recommend creating scope for the development of new organisational models, in which circus artists themselves have control over their long-term artistic development. In order to achieve that, there is a need for knowledge sharing and R&D in this area, a need that can be met by overarching organisations (Circuscentrum, in cooperation with the Flanders Arts Institute and Cultuurloket). In the short term, there is a need for optimisation by communicating the opportunities that currently exist under the decree. In the longer term, a revision of the decree may provide an approach that is more in line with the need for a diversity of organisational models.

- the circus should be recognised as a form of intangible heritage and initiatives should be implemented in order to ensure artistic knowledge sharing among circus artists and companies.

To make careers environmentally sustainable, our suggestion is that:

- for environmental sustainability to be included as a consideration (eligibility condition, criterion, etc.) within policy frameworks.

- good practices should be shared and artistic and organisational experimentation enabled, and that circus organisations should be guided in the direction of cross-sector networking and tools.

To make careers humanly sustainable, our suggestion is that:

- a strategy and an action plan be developed to ensure inclusion at the sector level.

- new formats for supporting the work-life balance of circus artists should be developed.

- training opportunities for children should be provided at traditional circuses and that awareness of the importance of this should be raised amongst government and overarching organisations.

- safety nets be established to reduce the physical and mental risks incurred by artists.

- career conversion opportunities and redirection pathways should be highlighted.

To make careers socially sustainable, our suggestion is that:

- an inclusive approach should be taken when setting up networking opportunities.

- support should be given for the development of networks amongst circus artists by providing a diversity of organisations that can support artists in doing so and that opportunities should be provided so that artists/companies themselves can develop sufficient capacity (i.e. time and expertise) to enable networks to be developed. Sustained organisational support is important in that regard.

Circusmagazine is the quarterly magazine for circus art. In a contemporary and idiosyncratic way, it reports on the past, present and future of the circus world in Flanders and beyond.

Subscribe here